Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry

Although a range of enzymes have been explored since my original creation and development of ZooMS collagen fingerprinting approximately 20 years ago (Buckley 2008), the most common is trypsin, molecular scissors that cut at positions most evenly spread across a wide range of proteins including collagen. Being the most abundant protein in the animal kingdom and particularly dominant in bone, collagen was long considered genetically uninformative due to the sequence rules required for maintaining its highly repetitive triple helical structure. Fortunately at least one of the three strands of the helix is a lot more free from these rules, giving us evolutionary (and therefore taxonomically) useful information which I developed ZooMS to harness. The main advantages of ZooMS over other techniques are its amenability to high-throughput analyses, relatively low costs and high success rates in archaeological material. Of course how well the proteins preserve (collagens or a wide range of others of potential interest) is affected by a range of taphonomic and environmental factors, such as temperature (including burning), soil chemistry and moisture.

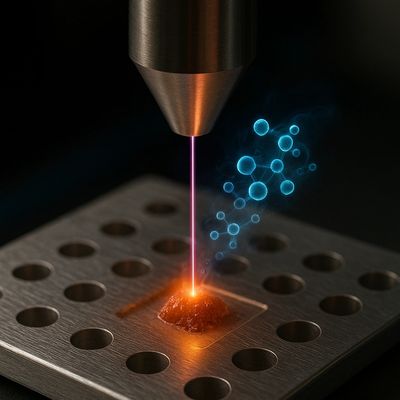

Collagen fingerprints can be retrieved after millions of years